But it is his sublime performance as Stephen Hawking in The Theory of Everything that has earned Redmayne a spot on Hollywood’s coveted A-list. The Oscar buzz started the moment the film screened at the Toronto Film Festival. “It means the world,” Redmayne has said repeatedly of the critical kudos the movie has received. But he was also quick to point out that “because of the stakes of the film” and the “utter relief” he felt when Hawking and his family said they enjoyed it, he just wants to do whatever he can to get people to go and see this “inspiring, unknown story.”

ANDREW GARFIELD: The last time I was with you was at the Toronto Film Festival, for the world premiere of The Theory of Everything. I just want to say—because it’s the truth—that there is nothing but freedom that I saw in your performance. I saw no stress, no fear. I didn’t see any acting. I saw a man in the heart of his craft, leaving his entire body—the parts of his body that he was allowed to use—and soul.

EDDIE REDMAYNE: Thank you for the kind words. That means a lot.

AG: I wanted to know how you felt that night, because it’s evident how personal this film was for you.

ER: There is something horrifically unnatural about actors watching themselves on a big screen with an audience. You end up scrutinizing all the things you are frustrated with. When you’re spending months trying to replicate and embody [Hawking’s] facial movements or his voice, you begin to believe you can get to what you see in the documentary, but you never do. The process of preparing for this film was particularly complicated because we weren’t shooting chronologically. We had to do this physical decline [out of sequence].

AG: And [there’s] the responsibility of playing not only a living, breathing human being, but this living, breathing human being.

ER: Stephen has so much humor. It’s very difficult for him to communicate—now he can only do so using an eye muscle—yet he has the most fiendish timing. I belly-laughed a lot in his presence. That’s something we really tried to bring into the film, to always find the positive. Hearing the audience laugh at that premiere, and to have them feel like they were allowed to laugh, despite the subject matter—a family dealing with gritty obstacles—made me so happy. Because that’s the feeling I had when I left my meeting with Stephen. He’s had a guillotine over his head since the age of 21, yet he lives each moment hopefully, and lives life with humor. When I saw the audience responding to those parts of the film, I was thrilled.

AG: I have chills hearing you talk about it. Much of that [laughter] has to do with the effervescence that you brought [to the role of] a strangely charismatic astrophysicist genius, with this lust and vitality for living, which it sounds like is his true essence.

ER: Hawking took on an idol-like status. When you’re in a room with him, he absolutely controls it. He really has an amazing strength, which can be difficult and complicated. He loves women, and women love him. You can see this glint in his eye.

AG: It’s clear that your core has shifted and your essence has deepened from spending time with this man. How has inhabiting him shifted Eddie?

ER: I met him five days before we started filming. That was after five months of prepping and reading everything, and, of course, desperately trying to comprehend as much astrophysics as I could—which is not very much. Because we weren’t shooting chronologically, I had to prep a performance much more technically than I’ve ever had to before. What scared me was [the possibility that] meeting him a few days before could have undermined all that, and I don’t mean just the physical side. What if there were parts of his character that didn’t ring true? Fortunately, what I gained from the experience was his humor and wit and joy of life, as well as minute physical things.

AG: When you first read the script, did you get the sense that this movie was going to be a massive healing experience?

ER: I met 30 to 40 people suffering from motor neuron disease [which afflicts Hawking] and their families. One person described it as being in a prison cell where your walls just get smaller every day. Your brain is obviously functioning entirely, and as a consequence, there’s this sort of timer on your life. Time shifts, so every hour is like a day, every day is like a week, and every week is like a month. I’m such a culprit for getting caught up in my own foibles. But you have to realize just how damn lucky you are and make the most of every minute. I have to keep reminding myself, because you quickly get back to the same pattern of frustrations.

AG: You take on a project that has deep meaning to you and you experience so much personal growth, then old habits come back in, and suddenly you’re buying Us Weekly…

ER: My favorite, FYI.

AG: Singing to, I don’t know, to a third-rate Rihanna song as opposed to a first-rate Rihanna song.

ER: Or maybe a little Swift.

AG: I know that

Stephen has seen the film. Who else?

ER: Stephen and Jane [Hawking’s ex-wife] and the family were the people that Felicity [Jones, who plays Jane] and I were most nervous about seeing the film, because their story is an incredibly passionate and inspirational one. It feels like such a responsibility, particularly when they had been very generous with their time. I’d be curious to see Dr. Katie Sidle, an amazing doctor, and the clinical nurse, Jan Clarke, from the Queen Square Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases [where Redmayne interacted with MND patients] watching it. I don’t know how you feel about promoting films, Garf—but for once, when you care about a story and you want people to see the story because it’s affected you and you want it to affect others, I feel quite invigorated doing press.

AG: What I’m hearing you say is you’re having the experience of serving something greater. You get to show up for all of those with ALS, for all who have had struggles with living their fullest life. The main testament to the soul of the film is the fact that Hawking and the family responded the way they did. That’s kind of “game over,” you know what I mean? So I have no fear. You fear away.

ER: Thank you, mate. You know I’ll fear away; that’s my modus operandi. Even though the story is very specific, it’s symbolic of how people deal with obstacles in their lives. Jane Hawking ended up being a huge advocate for [the rights of the disabled], making places accessible for people in wheelchairs. Because Stephen was so iconic, she really broke boundaries.

Redmayne prepared for his role for five months prior to filming.

AG: Can I ask about the balance you had to strike between technique and spontaneity? When an actor plays a real human being, there’s an expectation of how they are going to do a good impression or some kind of mimicry. I know that everyone who sees the film feels

you don’t just inhabit the body; you inhabit the soul. Can you talk a little bit about that?

ER: I said to James [Marsh, the director] I’d need time [to prepare], and he gave me four to five months. Hawking was diagnosed with ALS when he was 21. His disease is entirely secondary [to his life] as far as he’s concerned. Similarly, I wanted to make all the physical elements of the performance so embedded and second nature. Some of my favorite moments were improvised. The emotional lines of the film came from reading Jane and Stephen’s books, but also the patients that I met.

AG: This is a hard question: We get to have these incredible, soul-enriching experiences. Do you have any practices to keep yourself in that deeper, more aware and conscious place?

ER: The answer is I don’t have an answer, and like you I am still trying to figure it out. I guess the answer is making sure you’re fulfilled in other interests in your life.

AG: You were an art history major back in your Cambridge days.

ER: I was asked in an interview this morning what I would be if I wasn’t an actor, and I said a curator. But I think that was far too hyperbolic.

AG: No, buddy.

I’ve spent some time with you in the Victoria and Albert Museum, and it’s really awesome to walk around with you.

I was with a top-class tour guide because your knowledge and passion are so deep. I remember when you would talk about

Red [the Tony-winning Broadway show] and Rothko, your blood was pulsing. You were a man at the exact right place in his life, doing exactly what he should be doing.

ER:

What I loved about Red is that it was a meeting of all the things I was interested in.

That rare moment when all the stars align.

AG: What happens when you have

the opposite experience in work?

ER: You go home, drink a lot of red wine, cuddle up to your teddy bear, and cry. There are some amazing directors out there, but they have a set of ground rules that work brilliantly for some people, but that often make me tense up and go back to that safe, crap place. The only thing I’ve learned in 10 years is if you don’t feel free to mess up and try new things—even if the director has the most brilliant reputation—then it’s never going to work. If you don’t feel like you can take shots that are crazy and bold and will probably fail, then that’s not the right person to be working with.

AG: I don’t know about you, but I’ve been having a lot of conversations with people of our generation. Possibly because of how competitive it is out there, in terms of the economy and job availability, there’s not a lot of stopping, or just allowing yourself to be enough as you are—without constantly needing to prove something.

ER: I was reading an interview with Rachel Weisz a few years ago and she said, “Every time I finish a job, I think I’m never going to get hired again,” and I was like, “Come on, you’re Rachel Weisz.” But I absolutely get it. Because I think if you’re lucky to do this thing professionally, that you loved doing as a child, and you don’t feel like you’re qualified—it’s that old shtick of waiting to be found out. The idea that you do this job and get paid for it doesn’t seem like it should be allowed.

AG: We’ve mostly shared time in London and LA. What are your feelings about New York City?

ER: I’m weirdly obsessed. When I was 13 or 14, I had a calendar of black and white New York photos and was endlessly trying to do drawings of them. And then my mum took me to New York, and we were lucky enough to stay in this hotel on the 21st floor. I opened the windows and the curtains, and there was St. Patrick’s Cathedral, with all the high-rise buildings flying up above it. I kid you not, my knees buckled. I find New York the most electric, enlivening place. There’s something about the theater world, too. In London the theaters are geographically spread out so there’s no sense of community. In New York, the theaters back onto each other so you’d come out after doing the Rothko play, and Lucy Liu would be walking out from God of Carnage, and you were sharing this back alley, all of you together.

AG: There’s a way to create community in theater that you can’t so much in film because, maybe, there’s just too much money involved.

ER: One of the great New York experiences is where you have a dress rehearsal before your first preview. It’s in the middle of the day so all the other actors and people from other shows can come. I remember Alfred Molina saying, “Ed, don’t expect this audience to be like any other. They will be the most generous audience you’ve ever heard.” We’re so lucky to have the experience of performing on Broadway, or the experience of living in LA. When we started, I would turn up in my really shoddy rental car and park it as far from Paramount as possible, and walk in and pretend as if I knew what I was talking about—you pretend to be living one life when you actually can’t afford to pay your rent. It’s something that has really made our group of friends; it’s so amazing to be able to share that with people.

AG: It’s unlike anything we were raised in, right?

ER: It’s also beyond anything we could have dreamed.

AG: You’ve been so inspired by Jane Hawking and her incredible work.

What charities are you involved with right now?

ER: For the past year and a half [I’ve been] working with people who suffer from motor neuron disease [Hawking’s affliction], and I’m one of the patrons of the

MNDA, which is the British association. This disease has been around for over a hundred years or longer, and we’re not any closer to finding a cure. That has a lot to do with the fact that not many people have it, so pharmaceutical companies won’t invest in research. [Recently] there was the

Ice Bucket Challenge, and people were critical of it because everyone was jumping on the bandwagon. But it was raising awareness. I think the disease has a branding problem because it’s called different things, like motor neuron disease, MND, in the UK, ALS, Lou Gehrig’s disease. The fact is [the Ice Bucket Challenge] brought attention to the disease. I hope The Theory of Everything will act similarly. The other charity I’ve been working with is the

Teenage Cancer Trust in London. For years, I’ve been going to the wards and meeting young people. I feel really privileged in that sense.

AG: Nice, man—you’re a hero. (

source via)

I think if you’re lucky to do this thing professionally, that you loved doing as a child, and you don’t feel like you’re qualified—it’s that old shtick of waiting to be found out. The idea that you do this job and get paid for it doesn’t seem like it should be allowed. (x)

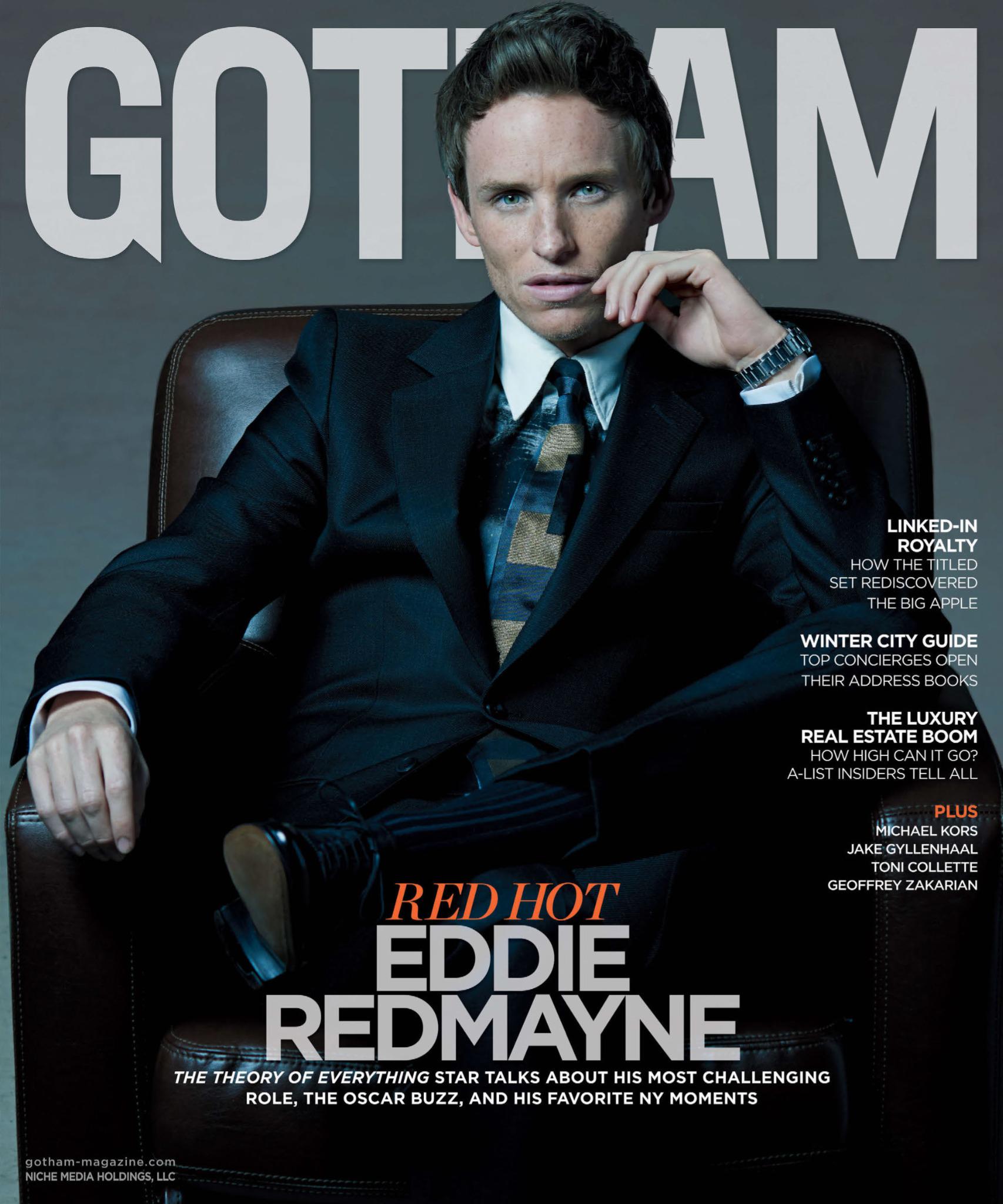

Just Jared:

Eddie Redmayne Gets Interviewed by BFF Andrew Garfield for 'Gotham' Magazine Cover Story

Quotes from the interview and magazine scans