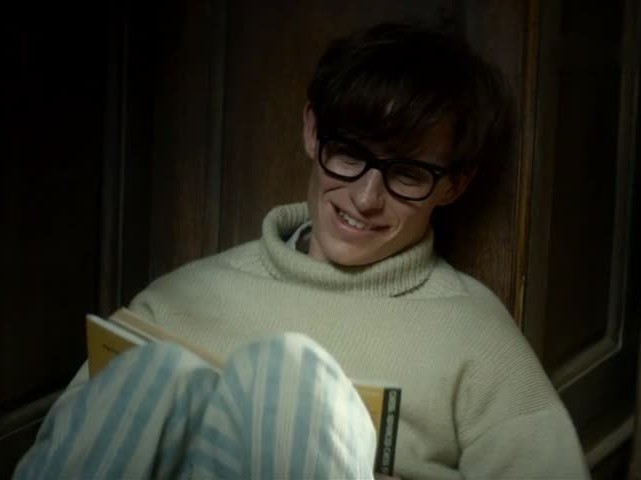

Our Best Actor winner is Eddie Redmayne for The Theory of Everything. (x)

Sunday afternoon, the New York Film Critics Online organization voted on and announced its 2014 award winners, including "Boyhood" as Best Picture. In the past, NYFCO’s echoed the major contenders in each category, adding

to a snowball effect for films like previously named Best Pictures like "12 Years a Slave," "Zero Dark Thirty," and

"The Artist." This year sticks to the trend, with familiar picks popping up in the organization's major categories. (x)

BY JANE HAWKING 12/5/14 AT 3:20 PM

We never spoke to each other, but I am sure this early memory is to be trusted, because Stephen was a pupil at the school for a term at that time before going to a preparatory school a few miles away.

Last year, the New York Film Critics Online picked eventual Oscar winner "12 Years a Slave" as Best Picture and foresaw three of the four acting winners as well; their love of "12 Years" saw them go for the leading performance of Chiwetel Ejiofor over Matthew McConaughey ("Dallas Buyers Club."

This year, they have followed in the path of the Gotham print scribes by naming "Boyhood" as the best film of the year. Likewise, they endorsed three of the four performances chosen by the New York Film Critics Circle, differing only on Best Actor. - winners list here

This year, they have followed in the path of the Gotham print scribes by naming "Boyhood" as the best film of the year. Likewise, they endorsed three of the four performances chosen by the New York Film Critics Circle, differing only on Best Actor. - winners list here

New Poster (x)

True story - Newsweek:

How I Fell In Love With Stephen HawkingBY JANE HAWKING 12/5/14 AT 3:20 PM

The story of my life with Stephen Hawking began in the summer of 1962, though possibly it began ten or so years earlier than that without my being aware of it.

When I entered St Albans High School for Girls as a seven-year-old first-former in the early Fifties, there was for a short spell a boy with floppy, golden-brown hair who used to sit by the wall in the next-door classroom. The school took boys, including my brother Christopher, in the junior department, but I only saw the boy with the floppy hair on the occasions when, in the absence of our own teacher, we first-formers were squeezed into the same classroom as the older children.We never spoke to each other, but I am sure this early memory is to be trusted, because Stephen was a pupil at the school for a term at that time before going to a preparatory school a few miles away.

It was a school friend of mine, Diana King, who first pointed Stephen out to me in that summer of 1962 when, after the exams, she, my best friend Gillian and I were enjoying the blissful period of semi-idleness before the end of term. Diana and Gillian were leaving school that summer, while I was to stay on as Head Girl for the autumn term, when I would be applying for university entrance.

That Friday afternoon we collected our bags and, adjusting our straw boaters, we decided to drift into town for tea. We had scarcely gone a hundred yards when a strange sight met our eyes on the other side of the road: there, lolloping along in the opposite direction, was a young man with an awkward gait, his head down, his face shielded from the world under an unruly mass of straight brown hair. Immersed in his own thoughts, he looked neither to right nor left, unaware of the group of schoolgirls across the road.

He was an eccentric phenomenon for strait-laced, sleepy St Albans. Gillian and I stared rather rudely in amazement but Diana remained impassive.

“That’s Stephen Hawking. I’ve been out with him actually,” she announced to her speechless companions.

“No! You haven’t!” we laughed incredulously.

“Yes I have. He’s strange but very clever, he’s a friend of Basil’s [her brother]. He took me to the theatre once, and I’ve been to his house. He goes on ‘Ban the Bomb’ marches.”

Raising our eyebrows, we continued into town, but I did not enjoy the outing because, without being able to explain why, I felt uneasy about the young man we had just seen. Perhaps there was something about his very eccentricity that fascinated me in my rather conventional existence. Perhaps I had some strange premonition that I would be seeing him again. Whatever it was, that scene etched itself deeply on my mind.

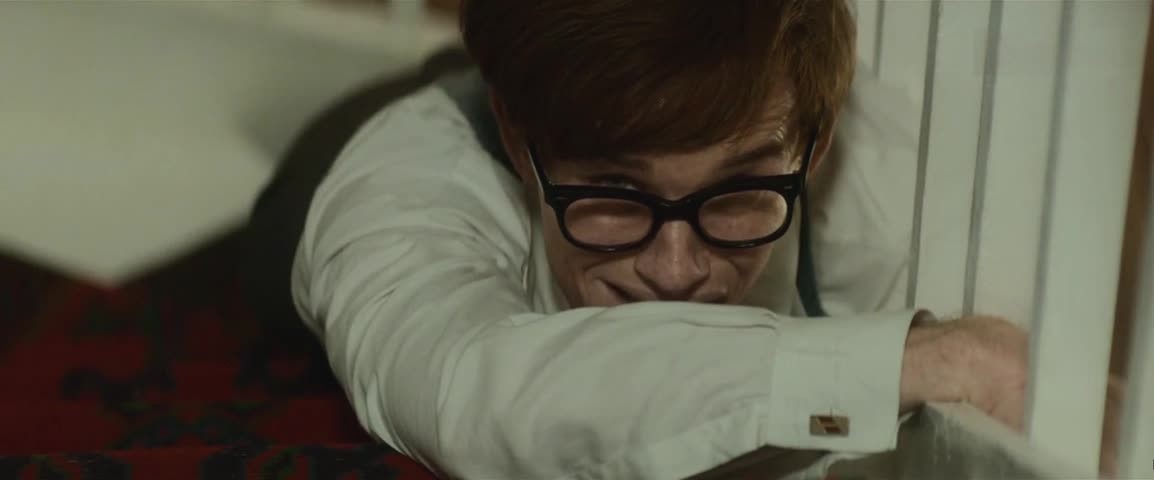

When, a few months later, Diana invited me to a New Year’s party which she was giving with her brother, I went along, neatly dressed in a dark-green silky outfit – synthetic, of course – with my hair back-brushed in an extravagant bouffant roll, inwardly shy and very unsure of myself. There, slight of frame, leaning against the wall in a corner with his back to the light, gesticulating with long thin fingers as he spoke – his hair falling across his face over his glasses – and wearing a dusty black-velvet jacket and red-velvet bow tie, stood Stephen Hawking, the young man I had seen lolloping along the street in the summer.

Standing apart from the other groups, he was talking to an Oxford friend, explaining that he had begun research in cosmology in Cambridge – not, as he had hoped, under the auspices of Fred Hoyle, the popular television scientist, but with the unusually named Dennis Sciama. At first, Stephen had thought his unknown supervisor’s name was Skeearma, but on his arrival in Cambridge he had discovered that the correct pronunciation was Sharma.

He admitted that he had learnt with some relief, the previous summer – when I was doing A levels – that he had gained a First Class degree at Oxford. This was the happy result of a viva, an oral exam, conducted by the perplexed examiners to decide whether the singularly inept candidate whose papers also revealed flashes of brilliance should be given a First, an Upper Second or a Pass degree, the latter being tantamount to failure.

He nonchalantly informed the examiners that if they gave him a First he would go to Cambridge to do a PhD, thus giving them the opportunity of introducing a Trojan horse into the rival camp, whereas if they gave him an Upper Second (which would also allow him to do research), he would stay in Oxford. The examiners played for safety and gave him a First.

Stephen went on to explain to his audience of two, his Oxford friend and me, how he had also taken steps to play for safety, realizing that it was extremely unlikely that he would get a First at Oxford on the little work he had done. He had never been to a lecture – it was not the done thing to be seen working when friends called – and the legendary tale of his tearing up a piece of work and flinging it into his tutor’s wastepaper basket on leaving a tutorial is quite true.

Fearing for his chances in academia, Stephen had applied to join the Civil Service and had passed the preliminary stages of selection at a country-house weekend, so he was all set to take the Civil Service exams just after Finals. One morning he woke late as usual, with the niggling feeling that there was something he ought to be doing that day, apart from his normal pursuit of listening to his taped recording of the entire Ring Cycle.

As he did not keep a diary but trusted everything to memory, he had no way of finding out what it was until some hours later, when it dawned on him that that day was the day of the Civil Service exams.

I listened in amused fascination, drawn to this unusual character by his sense of humor and his independent personality. His tales made very appealing listening, particularly because of his way of hiccoughing with laughter, almost suffocating himself, at the jokes he told, many of them against himself.

Clearly here was someone, like me, who tended to stumble through life and managed to see the funny side of situations. Someone who, like me, was fairly shy, yet not averse to expressing his opinions; someone who unlike me had a developed sense of his own worth and had the effrontery to convey it.

As the party drew to a close, we exchanged names and addresses, but I did not expect to see him again, except perhaps casually in passing. The floppy hair and the bow tie were a façade, a statement of independence of mind, and in future I could afford to overlook them, as Diana had, rather than gape in astonishment, if I came across him again in the street.

- source

(An edited version of the first chapter of Travelling to Infinity: The True Story behind The Theory of Everything by Jane Hawking.)

“That’s Stephen Hawking. I’ve been out with him actually,” she announced to her speechless companions.

“No! You haven’t!” we laughed incredulously.

“Yes I have. He’s strange but very clever, he’s a friend of Basil’s [her brother]. He took me to the theatre once, and I’ve been to his house. He goes on ‘Ban the Bomb’ marches.”

Raising our eyebrows, we continued into town, but I did not enjoy the outing because, without being able to explain why, I felt uneasy about the young man we had just seen. Perhaps there was something about his very eccentricity that fascinated me in my rather conventional existence. Perhaps I had some strange premonition that I would be seeing him again. Whatever it was, that scene etched itself deeply on my mind.

When, a few months later, Diana invited me to a New Year’s party which she was giving with her brother, I went along, neatly dressed in a dark-green silky outfit – synthetic, of course – with my hair back-brushed in an extravagant bouffant roll, inwardly shy and very unsure of myself. There, slight of frame, leaning against the wall in a corner with his back to the light, gesticulating with long thin fingers as he spoke – his hair falling across his face over his glasses – and wearing a dusty black-velvet jacket and red-velvet bow tie, stood Stephen Hawking, the young man I had seen lolloping along the street in the summer.

Standing apart from the other groups, he was talking to an Oxford friend, explaining that he had begun research in cosmology in Cambridge – not, as he had hoped, under the auspices of Fred Hoyle, the popular television scientist, but with the unusually named Dennis Sciama. At first, Stephen had thought his unknown supervisor’s name was Skeearma, but on his arrival in Cambridge he had discovered that the correct pronunciation was Sharma.

He admitted that he had learnt with some relief, the previous summer – when I was doing A levels – that he had gained a First Class degree at Oxford. This was the happy result of a viva, an oral exam, conducted by the perplexed examiners to decide whether the singularly inept candidate whose papers also revealed flashes of brilliance should be given a First, an Upper Second or a Pass degree, the latter being tantamount to failure.

He nonchalantly informed the examiners that if they gave him a First he would go to Cambridge to do a PhD, thus giving them the opportunity of introducing a Trojan horse into the rival camp, whereas if they gave him an Upper Second (which would also allow him to do research), he would stay in Oxford. The examiners played for safety and gave him a First.

Stephen went on to explain to his audience of two, his Oxford friend and me, how he had also taken steps to play for safety, realizing that it was extremely unlikely that he would get a First at Oxford on the little work he had done. He had never been to a lecture – it was not the done thing to be seen working when friends called – and the legendary tale of his tearing up a piece of work and flinging it into his tutor’s wastepaper basket on leaving a tutorial is quite true.

Fearing for his chances in academia, Stephen had applied to join the Civil Service and had passed the preliminary stages of selection at a country-house weekend, so he was all set to take the Civil Service exams just after Finals. One morning he woke late as usual, with the niggling feeling that there was something he ought to be doing that day, apart from his normal pursuit of listening to his taped recording of the entire Ring Cycle.

As he did not keep a diary but trusted everything to memory, he had no way of finding out what it was until some hours later, when it dawned on him that that day was the day of the Civil Service exams.

I listened in amused fascination, drawn to this unusual character by his sense of humor and his independent personality. His tales made very appealing listening, particularly because of his way of hiccoughing with laughter, almost suffocating himself, at the jokes he told, many of them against himself.

Clearly here was someone, like me, who tended to stumble through life and managed to see the funny side of situations. Someone who, like me, was fairly shy, yet not averse to expressing his opinions; someone who unlike me had a developed sense of his own worth and had the effrontery to convey it.

As the party drew to a close, we exchanged names and addresses, but I did not expect to see him again, except perhaps casually in passing. The floppy hair and the bow tie were a façade, a statement of independence of mind, and in future I could afford to overlook them, as Diana had, rather than gape in astonishment, if I came across him again in the street.

- source

(An edited version of the first chapter of Travelling to Infinity: The True Story behind The Theory of Everything by Jane Hawking.)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Your comment can be published after moderation